Meta Transactions

NEP-366 introduced the concept of meta transactions to Near Protocol. This feature allows users to execute transactions on NEAR without owning any gas or tokens. In order to enable this, users construct and sign transactions off-chain. A third party (the relayer) is used to cover the fees of submitting and executing the transaction.

The MVP for meta transactions is currently in the stabilization process. Naturally, the MVP has some limitations, which are discussed in separate sections below. Future iterations have the potential to make meta transactions more flexible.

Overview

Credits for the diagram go to the NEP authors Alexander Fadeev and Egor

Uleyskiy.

Credits for the diagram go to the NEP authors Alexander Fadeev and Egor

Uleyskiy.

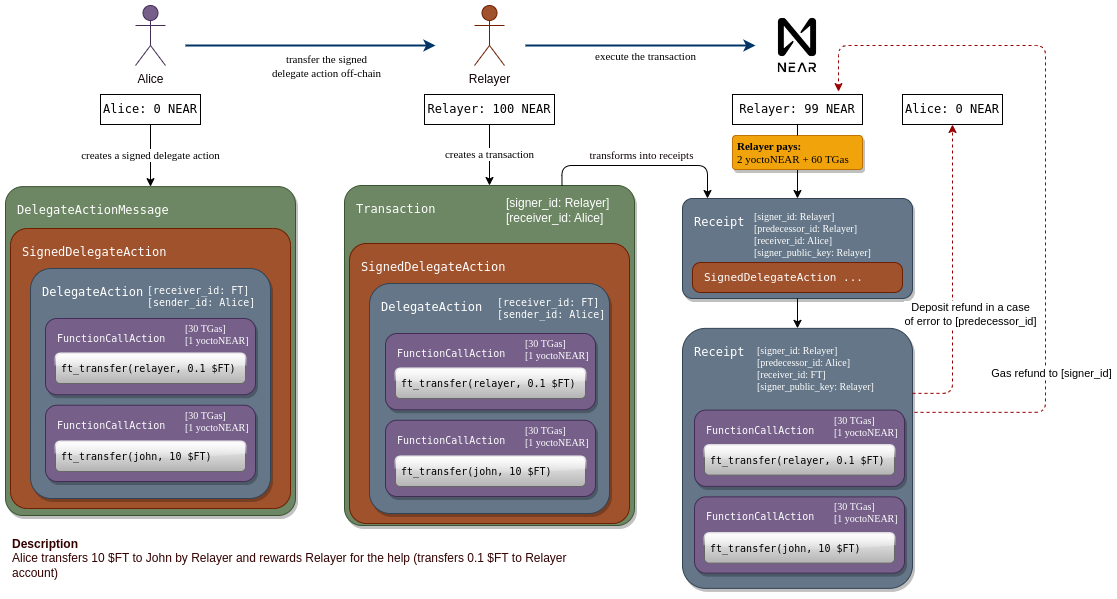

The graphic shows an example use case for meta transactions. Alice owns an

amount of the fungible token $FT. She wants to transfer some to John. To do

that, she needs to call ft_transfer("john", 10) on an account named FT.

In technical terms, ownership of $FT is an entry in the FT contract's storage

that tracks the balance for her account. Note that this is on the application

layer and thus not a part of Near Protocol itself. But FT relies on the

protocol to verify that the ft_transfer call actually comes from Alice. The

contract code checks that predecessor_id is "Alice" and if that is the case

then the call is legitimately from Alice, as only she could create such a

receipt according to the Near Protocol specification.

The problem is, Alice has no NEAR tokens. She only has a NEAR account that

someone else funded for her and she owns the private keys. She could create a

signed transaction that would make the ft_transfer("john", 10) call. But

validator nodes will not accept it, because she does not have the necessary Near

token balance to purchase the gas.

With meta transactions, Alice can create a DelegateAction, which is very

similar to a transaction. It also contains a list of actions to execute and a

single receiver for those actions. She signs the DelegateAction and forwards

it (off-chain) to a relayer. The relayer wraps it in a transaction, of which the

relayer is the signer and therefore pays the gas costs. If the inner actions

have an attached token balance, this is also paid for by the relayer.

On chain, the SignedDelegateAction inside the transaction is converted to an

action receipt with the same SignedDelegateAction on the relayer's shard. The

receipt is forwarded to the account from Alice, which will unpacked the

SignedDelegateAction and verify that it is signed by Alice with a valid Nonce

etc. If all checks are successful, a new action receipt with the inner actions

as body is sent to FT. There, the ft_transfer call finally executes.

Relayer

Meta transactions only work with a relayer. This is an application layer

concept, implemented off-chain. Think of it as a server that accepts a

SignedDelegateAction, does some checks on them and eventually forwards it

inside a transaction to the blockchain network.

A relayer may choose to offer their service for free but that's not going to be financially viable long-term. But they could easily have the user pay using other means, outside of Near blockchain. And with some tricks, it can even be paid using fungible tokens on Near.

In the example visualized above, the payment is done using $FT. Together with

the transfer to John, Alice also adds an action to pay 0.1 $FT to the relayer.

The relayer checks the content of the SignedDelegateAction and only processes

it if this payment is included as the first action. In this way, the relayer

will be paid in the same transaction as John.

Note that the payment to the relayer is still not guaranteed. It could be that Alice does not have sufficient FT balance of Alice first.

Unfortunately, this still does not guarantee that the balance will be high enough once the meta transaction executes. The relayer could waste NEAR gas without compensation if Alice somehow reduces her $FT balance in just the right moment. Some level of trust between the relayer and its user is therefore required.

The vision here is that there will be mostly application-specific relayers. A general-purpose relayer is difficult to implement with just the MVP. See limitations below.

Limitation: Single receiver

A meta transaction, like a normal transaction, can only have one receiver. It's possible to chain additional receipts afterwards. But crucially, there is no atomicity guarantee and no roll-back mechanism.

For normal transactions, this has been widely accepted as a fact for how Near Protocol works. For meta transactions, there was a discussion around allowing multiple receivers with separate lists of actions per receiver. While this could be implemented, it would only create a false sense of atomicity. Since each receiver would require a separate action receipt, there is no atomicity, the same as with chains of receipts.

Unfortunately, this means the trick to compensate the relayer in the same meta

transaction as the serviced actions only works if both happen on the same

receiver. In the example, both happen on FT and this case works well. But it

would not be possible to send $FT1 and pay the relayer in $FT2. Nor could one

deploy a contract code on Alice and pay in $FT in one meta transaction. It

would require two separate meta transactions to do that. Due to timing problems,

this again requires some level of trust between the relayer and Alice.

A potential solution could involve linear dependencies between the action receipts spawned from a single meta transaction. Only if the first succeeds, will the second start executing, and so on. But this quickly gets too complicated for the MVP and is therefore left open for future improvements.

Constraints on the actions inside a meta transaction

A transaction is only allowed to contain one single delegate action. Nested delegate actions are disallowed and so are delegate actions next to each other in the same receipt.

Nested delegate actions have no known use case and it would be complicated to implement. Consequently, it was omitted.

For delegate actions beside each other, there was a bit of back and forth during the NEP-366 design phase. The potential use case here is essentially the same as having multiple receivers in a delegate action. Naturally, it runs into all the same complications (false sense of atomicity) and ends with the same conclusion: Omitted from the MVP and left open for future improvement.

Limitation: Accounts must be initialized

Any transaction, including meta transactions, must use NONCEs to avoid replay attacks. The NONCE must be chosen by Alice and compared to a NONCE stored on chain. This NONCE is stored on the access key information that gets initialized when creating an account.

Implicit accounts don't need to be initialized in order to receive NEAR tokens, or even FT but no NONCE is stored on chain for them. This is problematic because we want to enable this exact use case with meta transactions, but we have no NONCE to create a meta transaction.

For the MVP, the proposed solution, or work-around, is that the relayer will

have to initialize the account of Alice once if it does not exist. Note that

this cannot be done as part of the meta transaction. Instead, it will be a

separate transaction that executes first. Only then can Alice even create a

SignedDelegateAction with a valid NONCE.

Once again, some trust is required. If Alice wanted to abuse the relayer's helpful service, she could ask the relayer to initialize her account. Afterwards, she does not sign a meta transaction, instead she deletes her account and cashes in the small token balance reserved for storage. If this attack is repeated, a significant amount of tokens could be stolen from the relayer.

One partial solution suggested here was to remove the storage staking cost from accounts. This means there is no financial incentive for Alice to delete her account. But it does not solve the problem that the relayer has to pay for the account creation and Alice can simply refuse to send a meta transaction afterwards. In particular, anyone creating an account would have financial incentive to let a relayer create it for them instead of paying out of their own pockets. This would still be better than Alice stealing tokens but fundamentally, there still needs to be some trust.

An alternative solution discussed is to do NONCE checks on the relayer's access key. This prevents replay attacks and allows implicit accounts to be used in meta transactions without even initializing them. The downside is that meta transactions share the same NONCE counter(s). That means, a meta transaction sent by Bob may invalidate a meta transaction signed by Alice that was created and sent to the relayer at the same time. Multiple access keys by the relayer and coordination between relayer and user could potentially alleviate this problem. But for the MVP, nothing along those lines has been approved.

Gas costs for meta transactions

Meta transactions challenge the traditional ways of charging gas for actions. To see why, let's first list the normal flow of gas, outside of meta transactions.

- Gas is purchased (by deducting NEAR from the transaction signer account),

when the transaction is converted into a receipt. The amount of gas is

implicitly defined by the content of the receipt. For function calls, the

caller decides explicitly how much gas is attached on top of the minimum

required amount. The NEAR token price per gas unit is dynamically adjusted on

the blockchain. In today's nearcore code base, this happens as part of

verify_and_charge_transactionwhich gets called inprocess_transaction. - For all actions listed inside the transaction, the

SENDcost is burned immediately. Depending on the conditionsender == receiver, one of two possibleSENDcosts is chosen. TheEXECcost is not burned, yet. But it is implicitly part of the transaction cost. The third and last part of the transaction cost is the gas attached to function calls. The attached gas is also called prepaid gas. (Not to be confused withtotal_prepaid_exec_feeswhich is the implicitly prepaid gas forEXECaction costs.) - On the receiver shard,

EXECcosts are burned before the execution of an action starts. Should the execution fail and abort the transaction, the remaining gas will be refunded to the signer of the transaction.

Ok, now adapt for meta transactions. Let's assume Alice uses a relayer to execute actions with Bob as the receiver.

- The relayer purchases the gas for all inner actions, plus the gas for the delegate action wrapping them.

- The cost of sending the inner actions and the delegate action from the

relayer to Alice's shard will be burned immediately. The condition

relayer == Alicedetermines which actionSENDcost is taken (sirornot_sir). Let's call thisSEND(1). - On Alice's shard, the delegate action is executed, thus the

EXECgas cost for it is burned. Alice sends the inner actions to Bob's shard. Therefore, we burn theSENDfee again. This time based onAlice == Bobto figure outsirornot_sir. Let's call thisSEND(2). - On Bob's shard, we execute all inner actions and burn their

EXECcost.

Each of these steps should make sense and not be too surprising. But the

consequence is that the implicit costs paid at the relayer's shard are

SEND(1) + SEND(2) + EXEC for all inner actions plus SEND(1) + EXEC for

the delegate action. This might be surprising but hopefully with this

explanation it makes sense now!

Gas refunds in meta transactions

Gas refund receipts work exactly like for normal transaction. At every step, the difference between the pessimistic gas price and the actual gas price at that height is computed and refunded. At the end of the last step, additionally all remaining gas is also refunded at the original purchasing price. The gas refunds go to the signer of the original transaction, in this case the relayer. This is only fair, since the relayer also paid for it.

Balance refunds in meta transactions

Unlike gas refunds, the protocol sends balance refunds to the predecessor (a.k.a. sender) of the receipt. This makes sense, as we deposit the attached balance to the receiver, who has to explicitly reattach a new balance to new receipts they might spawn.

In the world of meta transactions, this assumption is also challenged. If an inner action requires an attached balance (for example a transfer action) then this balance is taken from the relayer.

The relayer can see what the cost will be before submitting the meta transaction

and agrees to pay for it, so nothing wrong so far. But what if the transaction

fails execution on Bob's shard? At this point, the predecessor is Alice and

therefore she receives the token balance refunded, not the relayer. This is

something relayer implementations must be aware of since there is a financial

incentive for Alice to submit meta transactions that have high balances attached

but will fail on Bob's shard.

Function access keys in meta transactions

Assume alice sends a meta transaction and signs with a function access key. How exactly are permissions applied in this case?

Function access keys can limit the allowance, the receiving contract, and the contract methods. The allowance limitation acts slightly strange with meta transactions.

But first, both the methods and the receiver will be checked as expected. That is, when the delegate action is unwrapped on Alice's shard, the access key is loaded from the DB and compared to the function call. If the receiver or method is not allowed, the function call action fails.

For allowance, however, there is no check. All costs have been covered by the relayer. Hence, even if the allowance of the key is insufficient to make the call directly, indirectly through meta transaction it will still work.

This behavior is in the spirit of allowance limiting how much financial resources the user can use from a given account. But if someone were to limit a function access key to one trivial action by setting a very small allowance, that is circumventable by going through a relayer. An interesting twist that comes with the addition of meta transactions.